House Prices, Council Monopoly and a Historic Village

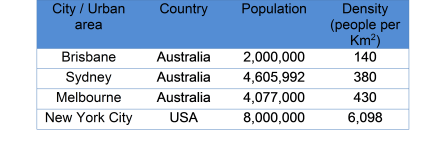

In January 2014 The Economist magazine completed a worldwide study[1] which produced an index of the cost of housing in real terms since 1975. Australia’s cost of housing was close to Britain, Japan and the United States until the early 1990’s. House prices from that point on remained above all these countries. The survey showed Australian cities are in the top five most expensive in the world even though our population is only within the top 60 countries. High house prices in Australia do not make intuitive sense as we have lots of land and a very small population. New York City population is about 8.3 million the greater Sydney areas population is about 4.5 million. The median 2 bedroom unit in NY is US$565,900[2] (AU$622,490), London is around AU$1 million[3] and in Sydney it is AU$819,000[4].

The importance of high Australian house prices relative to domestic wages and housing costs internationally does not appear to be well understood by the economic community. High house prices are a double edged sword, whereby there are winners and losers with any increase in house prices. People who own houses now will gain from an increase in house prices due to the increase in their capital value and be able to borrow against the new value of their asset, which will contribute to GDP through increased consumption or investment.

Housing costs comprise between 20% and 25%[5] of average living expenses, which makes up the largest proportion of household spending followed by food & non-alcoholic beverages (around 16%) and transport (around 15%)[6]. HIA Economics reports that after the year 2000 Australian house price ratio to household income has increased from its long run average of 2.5 to now sitting around 4[7].

Causes of High Property Prices

There are many factors impacting on the cost of housing and there is very little data collected on specific items. However, there are some significant issues in relation to the housing market supply and demand situation. A few of the significant drivers of housing demand are population, tax incentives, foreign investment and price. Normally, housing supply should increase to meet demand bringing the price back to the previous marginal cost of production.

The cost of production is increased through increases in the cost of capital and labour. The house construction costs are increased by an estimated 40%[8] due to Government taxes. These regulations could answer part of the question of why Australian house prices are very high. However, the cost of housing is much higher than the cost of construction therefore, there must be other powerful factors at play.

Supply Constraint

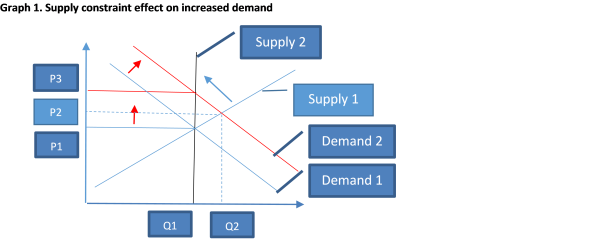

In a well-functioning market the supply of a product will increase when the demand increases the price. The increase in supply will bring the price back to market equilibrium which should result in the marginal revenue equal to marginal cost.

However, if there is a supply constraint the price would be above the market equilibrium price. As shown in Graph 1 below, supply 1 would be a free market supply resulting in the market price of P1. However, if supply is constrained by a force that is not affected by price then Supply 2 could be expected. The problem is when demand increases to Demand 2 for some reason the quantity supplied does not increase to Q2 as expected. The higher demand and no increase in supply forces the price up to P3 instead of P2.

Graph 1. Supply constraint effect on increased demand

Housing is a very geographically specific market which is largely driven by an individual’s weighing up of distance and time from key living requirements and the cost of the accommodation. Locations closest to the job centres are valued more than locations further away. Agglomeration effects lead to higher productivity and higher real wages in central business district (CBD) areas. Higher real wages in CBD locations can give people a higher willingness to pay for housing near the CBD further increasing housing demand close to the CBD.

Therefore, any supply constraints close to a CBD will have the largest effects on pricing. The demand close to the CBD can be reduced by efficient transport to homes located further away. The reduced travel time can shift demand to locations further away from the CBD. Therefore, the decision is whether the cost of the transport options are less than the benefits of living close to the CBD.

Why is supply inelastic?

Often the supply of available housing in the market is relatively inelastic because there are time lags between a change in price and an increase in the supply of new properties becoming available, other homeowners deciding to put their properties onto the market and availability of skilled labour. However, in Australia the supply of housing is highly controlled by local Councils.

Local Councils in Australia control the supply of housing and other development by deciding what land can be subdivided, what size the blocks can be, what proportion of land can be built on, how high a building can be and all other aspects of development of land and buildings.

Local Councils are effectively a monopoly provider of housing and business development. Monopolies tend to constrain supply to increase prices to capture higher rents or consumer surplus. This monopoly is no exception, a local Council may be motivated to constrain supply of development in its local area so residents (insiders) can capture rents. The higher the value of the insider’s property, the wealthier they feel and will tend to vote for the Councillor who made it happen.

The Council has an added incentive to increase local property values in that their rates base is calculated on the value of the land within the controlled area. Most Council members are also owners of property within the controlled area and therefore benefit directly through capital growth of their personal assets.

There are many pressures on the Council to make decisions in the interest of the insiders. Business owners in the local Council area may lobby the Council to restrict new entrants that could open in competition to insider businesses. Developers lobby the Council to restrict other outsider developers and approve their insider developments.

Queensland Example

An example of local Council constraining supply of development is the Brisbane restriction on demolishing old Queenslanders. In October of 1995, Brisbane City Council introduced ‘Gray Tape’ a blanket layer of protection over suburbs where the majority of homes had been built before the end of World War II. The rule is that any house built before World War II is not allowed to be demolished or removed. The pre-war homes are comparatively small wooden houses close to the city and encircle the Brisbane CBD. This restriction significantly reduced any development close to the CBD.

Map 1. Map of the Historic Village surrounding Brisbane CBD

There is in the order of 100 thousand[9] old Queenslanders stretching for about a 10 kilometres radius from the CBD. Map 1 below shows Brisbane CBD in red surrounded by the suburbs affected by the old Queenslander rules. People wishing to live in a new home have to live outside of these suburbs. There are a few new houses in these areas but very few. The new building approvals in these suburbs is at a low of 0.4% in 2012-13 down from 0.6% in 2003-04.

Graph 2. Demonstrating the slowing in growth of new dwellings in the protected suburbs of Brisbane

Source: ABS and Census data Dwellings, Location on Census Night & Building Approvals

Population density in Brisbane is very low for a city of its size as demonstrated in table 1 below. Low density housing would normally be expected to be lower cost than high density locations as the land would be too valuable to build large houses.

Table 1. Density of Brisbane compared to other cities

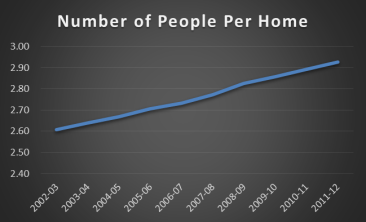

The low density and low growth in new housing may be explained by low population growth however this is not the case in Brisbane. Graph 3 below shows the number of people per household is growing. Population increasing faster than the housing supply would suggest the demand for housing in the area is growing faster than the supply. This will create increasing pressure on prices as expected.

Graph 3. Demonstrating the growth in the numbers of people per home in the protected suburbs of Brisbane

Source: ABS 3235 and Census data Dwellings, Location on Census Night & Building Approvals, OESR Population and Dwelling Profile Brisbane City Council April 2012[12]

As stated above, HIA Economics reports that Australian house price ratio to household income is currently around 4[13]. However, the house price to income ratio in Brisbane is much higher than the high level ratio reported in most statistics. Table 2 below demonstrates five standard 2013 job salaries against 413 house sales from 41 suburbs which have restrictions on old Queenslander houses. A person’s yearly salary would have to be over $180,000 to bring the ratio back to the national average of 4.

Table 2. House prices in the Brisbane Historic Village against standard Queensland wages

Heritage Value

What is heritage value?

Australia ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites), relates the heritage value of a place with the ‘cultural significance’ of a site (Marquis-Kyle and Walker 2004). The Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage Protection state:

“Queensland’s diverse heritage contributes to our sense of place, reinforces our identity and helps define what it means to be a Queenslander. Our heritage places have been shaped by Queensland’s history, environment, resources and people. They comprise places of cultural and natural significance that we want to keep, respect and pass on to future generations.”

Critically, this statement signifies a key element of cultural protections, ‘places of cultural and natural significance’. Every building ever built could someday be a place of historical value but we don’t restrict the removal or destruction of all buildings. Special controls of property is reserved for specific places which have some significant cultural value.

Cultural value is a difficult thing to define and measure and is a subjective value of one group over other people’s property. However, any definition of cultural value of a building should include the reason for keeping the building is to be able to look at the building and see how people lived in the time of its construction. Therefore, the building should be kept in the original condition without modern additions. Otherwise the building is just a new building with some old material attached.

An example of this is if a person takes a 1930’s car and turns it into a hot rod with a V8 motor and covered in chrome. This car no longer resembles the historic car it once was and gives no indication of what a 1930’s car was really like, it is now just a manifestation of someone’s imagination.

In the same vein, an old Queenslander raised expanded painted and covered in modern appliances is the Disney Land version of the original house. The heritage of the building is lost and therefore the heritage value is minimal. If the aim of the restrictions on removing old Queenslanders is to be able to remember where we came from then the houses should be maintained in the same condition they were when originally built.

There is a difference between selecting some special buildings that hold some historic value through kept knowledge or community experiences and just keeping any old building because it is old. Pictures 1 & 2 below show an example of what could be considered high and low heritage value buildings. However both buildings are protected from demolition to keep the heritage value.

Picture 1. 18 Donaldson Street Paddington offers over $600,000 2 bedrooms

Picture 2. Brisbane City Hall

How to keep cultural heritage?

The problem with maintaining houses as they were 100 years ago is the people living in them would have a very hard life. Original old Queenslanders did not have town water, electricity, sewer, air conditioning, carpet or many other modern comforts. Creative destruction has killed many old technologies to make way for the modern world increasing the wellbeing of all people in society. Not many people ride a horse to work or use a typewriter because modern cars and computers have taken their place. We certainly do not have laws to force people to use typewriters in their work place in order to remember how to use them or show our kids how things were in the old days. Our society still has typewriters in museums to maintain a historical record of how people operated in days before computers.

Creative destruction has now come for the homes we live in and the old Queenslander is no longer a suitable form of housing for a modern family. Many old cities around the world have areas of old houses in major cities that are maintained to display the way people lived hundreds of years ago. Mostly these places are in Europe where houses were built of stone which is hard to move to another location. London has decided to build very large sprawling cities with huge transport investments to move large amounts of people long distances past their historic village to the CBD. Long travel times to work make it an unpleasant place to live and work. Edinburgh in Scotland decided to build a new CBD across the river from the old CBD area. This is a very costly and disruptive way to approach the problem but the sheer quantity of very old buildings and associated infrastructure made it a viable option.

A way Queensland could keep the real historic value of the old Queenslanders is to have a Government sponsored historic village away from the Brisbane CBD. The beauty of an old Queenslander is it is possible to put it on a truck and move it to anywhere you want. The Government could purchase a large plot of land and some examples of the original old Queenslanders and develop a museum of old Queenslanders. The public could go to the village and get a real feel for how it was to live in Queensland 100 years ago. This solution would give maximum heritage value by maintaining the houses in the actual condition and filled with antiques of the era while minimising the cost to the State’s economy.

Cost of Current Restrictions

“Tradition is the living faith of the dead, traditionalism is the dead faith of the living. And, I suppose I should add, it is traditionalism that gives tradition such a bad name.”

― Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, The Vindication of Tradition: The 1983 Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities

Brisbane City Council’s blanket protection of old Queenslanders has no regard for cost benefit of heritage value, public goods or property rights of the people of Brisbane. Effectively a ban on development creating many costs and problems for the people of Brisbane in the name of heritage protection.

Reduced Property Rights

Strong property rights are one of the foundation stones of a good economy. Removing land owners right to develop land significantly reduces their property rights and freedom. There will always be some constraints on what you can do with your land or property however these constraints should be kept to a minimum. Removing the right for a person to remove a very old residential building and replace it with another residential building is not a reasonable constraint. Heritage protection that imposes the subjective values of one group of people over another group or persons property is a denial of consumer sovereignty. Also it imposes building technology and preferences from 100 years ago.

As Henry Ford said: “We don’t want tradition. We want to live in the present and the only history that is worth a tinker’s dam is the history we make today.” The current generation of people in Brisbane are not able to create their own traditions or heritage because the dead’s preferences are imposed on them.

Prosperity and property rights are inextricably linked, well-defined and strongly protected property rights is widely recognised to give individuals the right to use their resources as they see fit. Property users are then able to take full advantage of all the benefits and costs of employing those resources in a particular manner that provides them with highest outcomes. That translates into higher standards of living for all.

High Home Prices

The typical price for a small 2 bedroom, 100 year old wooden house on 200sqm near the Brisbane CBD is between $850,000 and $1.5 million. These high prices lead to upward pressure on wages which reduces the competitiveness of the city. Anyone who buys one of these houses as an investment will require high rents to recover the high capital invested.

Transport Costs

Due to the high cost of housing close to the city workers move further away from the CBD to purchase modern homes at more reasonable prices. These workers require transport to and from the CBD each day for work. The State Government has responsibility for most of the transport system in and around Brisbane. The State Government sees there are transport congestion problems and invests large amounts of money in new rail, roads, buses, tunnels and all supporting transport systems. In turn, workers likely pay tax to have a Government build large transport corridors through the old Queenslander ring (historic village).

The Government subsidises public transport in Brisbane by around $1.9 billion[14] of operating costs each year. Even a small percentage reduction in public transport costs would significantly reduce Government spending and, or the tax burden.

Increased Taxes

Due to the demand for transport to the CBD being higher than it otherwise would be the State Government has to spend more on transport. The increase in transport costs requires the State Government to increase taxes for the entire State of Queensland. The increase in taxes increases the cost of living and the cost of doing business in Queensland. The increased costs reduce competitiveness and disposable income of the taxpayers.

Time spent commuting

Now the CBD workers are spending more time being transported to and from work leaving less time to spend on work, recreation and family. Reduced time at work lowers output and reduced time for recreation or with family reduces the standard to living.

Environmental Damage

Increased urban sprawl causes environmental damage due to cutting down trees and destruction of natural habitat. Longer travel times to work increase fuel burned per trip. The trade-off between heritage and the environment should be considered in a cost benefit analysis of the options available. The suggested solution of a Government sponsored historic village would reduce the need for Brisbane to continue to sprawl into new ground surrounding the city while keeping the historical buildings available for future generations. The more people are able to build up the less they will have to build out therefore the more old Queenslanders that can be removed and the ground used for high rise residential apartments the less green field developments will be needed to house people.

Increased Cost of Production

The reduced supply of housing and business facilities increases the costs of living for all residence. Increased cost of living increases demand for wages and increases the cost of production. An example of this is a business owner has to pay high rent due to the shop owner requiring a return on the large cost of purchasing the shop and staff require high wages to pay for their home and transport costs.

Lower Standard of Living

Forcing people to live in old wooden houses or to travel for long periods of time and increasing the cost of living reduces those people’s standard of living. Not only are the houses small and old they are expensive to maintain or renovate. Any maintenance or renovations have to meet with the strict Council heritage rules. These constraints on what you can do and how you do it increase the cost of work on the old houses. Many people do not have the funds to meet the special heritage rules and therefore do not maintain or renovate their house for a long period of time. This leads to some people living in very poor conditions in the rundown houses which also reduce amenity for surrounding homes. The small size of the homes reduces the liveable space for families making for difficult living conditions.

Picture 3. An old Queenslander in Spring Hill

The picture above is a house in Spring Hill 1 kilometre from the Brisbane GPO a good location for a family to live with short travel distances to work. The inside of the house is unliveable, the driveway is shared with a neighbour and only 2 small bedrooms and was on the market in 2013 for $750,000. The renovation estimate from a builder was between $350,000 and $400,000 brining the full cost of living here to over a million dollars.

Many of these homes were built before modern safety standard and are full of dangerous things not allowed to be used in building today. These include lead paint and roofing, asbestos, poorly made stairs, thin floor boards from ants or worms, decaying stumps, old electrical wiring and retaining walls.

Picture 4. Two old Queenslanders in South Brisbane

Forcing people of Brisbane to live in such small homes or move out of the CBD is an inefficient way of operating a city and reduces the standard of living.

Reduced Investment

The high cost of living, high taxes and lack of density combine to produce a poor business environment. The heavy restrictions on development make it difficult to develop any business in Brisbane. For example, the Brisbane Convention Centre finds it difficult to attract events as there are not enough accommodation places available close to the venue[15]. The Convention Centre is surrounded by the old Queenslanders of South Brisbane and West End. If these suburbs were able to be developed there may be many more hotels built providing accommodation for large conventions.

Businesses in and around Brisbane are doing what they can with the buildings that are available. The picture below is an example of a business only 2 kilometres from Brisbane CBD. The picture demonstrates a business trying to work out of an old Queenslander protected building. This site is next to the bus stop, major hospital, large schools and close to South Bank. Other buildings near this building that are not on protected sites are 5 story high modern commercial buildings. The inability for the site to be developed means this business has to work out of an old house and other businesses are not able to build new facilities on this site. Businesses like this that are restricted from developing modern facilities will have reduced business as its building is not nice and other businesses cannot move in nearby to create agglomeration effects.

Picture 5. An old Queenslander being used as a business

High Opportunity Cost

There are significant opportunity costs related to this problem, including the commuting time of individuals. Money spent on transport infrastructure could be spent on other more productive items and lost business activity. One of the largest opportunity costs is the actual development itself. Allowing the removal of old Queenslanders in and around the CBD of Brisbane has potential to create a construction boom. Replacing six old houses with a high rise residential apartment building of between 50 – 100 floors with 4 apartments on each floor creates a space where six families lived to a space where 200 – 400 families can live.

Even if we allow for more parkland to provide nice surrounds for the buildings the use of the space close to the CBD would increase exponentially. The economic value derived from each hectare of land would be increased significantly. If each old Queenslander is valued at around $1 million and six of them are removed to allow one high rise residential building then $6 million is turned into 200 units valued at around $500,000 equals $100 million or 16 times more value from the same area of land.

Broader Implications

The old Queenslanders of Brisbane are only one example of the tools used by Local Council’s monopoly to restrict supply. This type of restriction and others like it are occurring all over Australia. All Local Councils are restricting supply of land and its use in one form or another. Restrictions on supply have the flow on effect of creating high costs. Australia-wide restrictions on development by Councils create large cities of urban sprawl and lack of development in the regional areas. Australia-wide restrictions lower productivity by constraining the agglomeration of economic activity, increase the costs of production for Australia and reduces our competitiveness with the rest of the world.

If the regional areas allowed large amounts of land to be developed then the price of the houses and therefore the cost of living in that area would be significantly lower than in the cities. However, the Council’s protection of insiders of the regional towns has created a property market that is similar price to cities. Given higher wages and better facilities in cities, individuals will likely be incentivised to live in cities. Picture 4 below shows an example of a 3 bedroom old Queenslander in Mackay selling for a similar price for one in Brisbane. Mackay is a regional town in Queensland which has increased demand form mining activity. However, the Local Council allowed the supply to increase the prices of houses would not be so high.

Picture 6. House for sale in Mackay $750,000

The pain of high house prices is reduced by Government spending ever-increasing amounts on transport to move more people longer distances faster. The alternative is to allow more development closer to the place of work and then people can walk or take a very short bus ride.

Allowing significant increases in the supply of residential and business buildings will reduce the cost of living and increase economic activity.

Possible Solutions

- Transfer the power from the Local Council to the State or Federal Government. The problem with this solution is there is no certainty the other levels of Government would make better decisions.

- Introduce an economic regulatory body that controls development approvals working with the Local Government. This solution could lead to larger problems as people game the regulations and do not work with the regulator.

- Federal and State Governments could work together to alter Local Government incentives to encourage them to allow more development. Local Governments rates are currently set on the basis of land values which as discussed above increases their incentive to restrict supply and increase values. Federal and State Governments would be able to derive a new and better incentive program for local Council to be able to profit from taking whatever action is required to remove restriction on supply of land and development.

Federal Treasury may be in the best place to design an incentive mechanism for the States delivered through a COAG agreement to push for reforms to local Council development approvals. In place of rates based on land value the Federal and State Government could provide funding to Councils based on the population numbers or economic activity in each Council region. This would achieve many aims of the Government including increased disbursement of the population, reduced congestion in cities, lower cost of living and increased economic activity.

Conclusion

There are some big problems in our housing supply and more work needs to be done to verify what the issues are and how we can effectively deal with the issues. Across Australia, Local Governments are holding back the development of Australia and reducing our standard of living.

[2] http://www.zillow.com/new-york-ny/home-values/

[3] http://www.londonpropertywatch.co.uk/s/ph?pc=LON&t=1-4b

[4] RP Data

[5] ABS 4130.0 – Housing Occupancy and Costs, 2011-12

[6] ABS 6530.0 – Housing Expenditure Survey, Australia 2009-10

[7] HIA Economics Group – December 2010 – House price to income ratio

[8] CIE 2011 report for HIA, “The Taxation Burden on the Australian New Housing Sector”

[9] Estimated by assuming half people in the affected area live in old Queenslanders population of 449,355 divided by half and then assuming 2.5 people live in each old Queenslander.

[10] ABS 3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2011-12

[11] http://www.citymayors.com/statistics/largest-cities-density-125.html

[13] HIA Economics Group – December 2010 – House price to income ratio

[14] The Queensland Rail (QR) and Translink financial statements show a grant of QR $1.75 billion and Translink $1.15 billion. Combined that makes $2.9 billion however this is not all public transport related. The detail of the subsidy is not provided in the financial statements therefore I made an assumption that two thirds of the grants ($1.9 billion) are related to public transport.

[15] Conversations with Brisbane Marketing and Brisbane Convention Centre staff

If you want peace, prepare for war

If you want peace, prepare for war

By Bradley Rogers April 2014

The Australian Government has decided to purchase some very expensive fighter jets. Tony Abbott and Defence Minister David Johnston have decided to purchase 58 F-35 joint strike fighters at a cost of $12.4 billion. This appears at first blush to be a high cost for a benefit we may (hopefully) never need to gain. However, as pointed out in Book 3 of Latin author Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus (Circa 390AD) – Si vis pacem, para bellum (if you want peace, prepare for war).

Anzac Day is fast approaching and it is a time to remember the terrible wars of the past in the hope we don’t allow ourselves to fall in to another war even more terrible than the last.

Defence is a very complex area of economics and as an ex-Army man I like to think of the possible cost benefit analysis of defence spending. Defence is one of the true public goods as economists define it and the benefit is the freedom of our population and the net present value of all future GDP’s. Therefore, on this simple assessment any amount is justifiable to spend on defence.

Defence Minister David Johnston will take a formal submission for the white paper to cabinet early next month, with the authors told to keep to two core pledges made by the Coalition in opposition: that there will be no cuts to defence spending; and that within a decade the defence budget should reach 2 per cent of gross domestic product.

Under Labor, the defence budget fell to its lowest level since before World War II, at less than 1.5 per cent of GDP. Defence experts estimate the current budget at about $26.5 billion this year – or 1.6 per cent of GDP. The new $50 billion figure is based on the Coalition meeting its pledge to increase defence spending to 2 per cent of GDP by 2023 and makes assumptions about the growth of the economy.1

There are currently some 2,892 ADF personnel deployed on 14 operations overseas and domestically in support of civil authorities in protecting Australia’s borders and in support of our interests in regional security. Current operations are part of a high tempo period that has seen the Australian Defence Force (ADF) undertake some 100 operations since 1999.

In Australia, the historical annual average defence spending since the end of the Vietnam War is approximately 2.2 per cent of Australia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Since 2000, the annual average has been around 1.8 per cent of GDP with the Defence budget remaining below 2 per cent of GDP across this period.

An ADF workforce of approximately 59,000 Permanent members will be maintained over the next decade. As shown in table 1 below Australia is very low on the list of world military powers but it does not have to be.

Table 1. World Defence Capability 2

| Military Spending ($M) | Total Population (M) | Active Personnel | Active Reserves | Tanks | Fighters | Navy | |

| USA | $620,600 | 317 | 1,430,000 | 850,880 | 8,325 | 2,271 | 473 |

| China | $166,000 | 1,350 | 2,285,000 | 2,300,000 | 9,150 | 1,170 | 520 |

| Russia | $90,700 | 146 | 766,000 | 2,485,000 | 15,500 | 736 | 352 |

| UK | $60,800 | 63 | 205,330 | 182,000 | 407 | 84 | 66 |

| Japan | $59,300 | 127 | 247,746 | 57,900 | 767 | 292 | 131 |

| France | $58,900 | 66 | 228,656 | 195,770 | 423 | 287 | 120 |

| India | $46,100 | 1,221 | 1,325,000 | 2,143,000 | 3,569 | 535 | 184 |

| Germany | $45,800 | 81 | 183,000 | 145,000 | 408 | 190 | 82 |

| South Korea | $31,700 | 49 | 640,000 | 2,900,000 | 2,346 | 409 | 166 |

| Australia | $26,200 | 22 | 58,000 | 44,240 | 59 | 78 | 53 |

Currently, Australia depends on its partners in the USA, UK, EU for its defence capability. However, defence is complex and tanks, planes and ships are only a part of the defence capability story. The other key defence capability issues are population, manufacturing and nuclear energy.

Population

Australia has a very small population compared to most countries of its size. Our defence is intrinsically tied to the size of our population as the larger the population the more people available to produce and use weapons of war.

Below, table 2 shows the numbers of people enlisted, killed and wounded in the last two world wars and then the number of people Australia could field with its current population.

Table 2. Estimated enlisted population possible in Australia 2014

| World War 1 (1914-18) | World War 2 (1939-45) | World War 3 (2014) | Proportion of Population | |

| Enlisted | 416,809 | 575,799 | 1,928,825 | 7.9% |

| Killed | 60,000 | 66,563 | 132,080 | 0.5% |

| Wounded | 156,000 | 39,429 | 222,974 | 0.9% |

| Population | 4,982,063 | 7,269,658 | 23,465,219 |

Table 1 above shows that China has a standing military of over 2.3 million people and a further 2.3 million of active reserves. Considering its population of over 1.4 billion people if it decided to develop a military of the same proportion of Australian defence in WWII (7.9%) it would have a defence force of over 106.9 million people. Australia has advantages in technology, training and allies but cannot escape the fact without a serious increase in population it has no defence.

A large increase in Australian population would reduce its defence spending per head of population, increase economic activity and provide it with a more diverse economy. Australia is a similar size geographically to the USA and has a wealth of resources to support a population of a similar size to the USA.

Australian population growth is only positive due to the immigration rate. The Australian birth rate is sitting at about 1.8 which is below replacement. Many people of the world would like to live in Australia and therefore it can be selective about who it allows to become residence. Contrary to many peoples beliefs increasing immigration increases the wealth of the country and each person, especially if the immigration is targeted at highly trained and educated people. Educated people who come to Australia start new business, buy a house and fill it with furniture. This extra economic activity will increase the GDP of the country.

Allowing big increases in Australian immigration would produce big increases in economic growth and assist in our defence.

Manufacturing

Australian manufacturing has been unprofitable for many years especially in the car manufacturing. The Federal Government supported the car manufacturing to ‘support jobs’ but it also supported our defence. In a world of no war Australia can import any cars or defence equipment it needs. However, if a war did break out in a big way the supply lines to the manufacturing countries would be cut. This is not a problem for cars but it is a problem when Australia needs to start producing more tanks, planes and ships in preparation for war.

A car manufacturing plant is capable of making many different types of machines at a high rate if configured in the right way. Maintaining the manufacturing industry in Australia provides it with a degree of ability to make machines of war if required.

The Australian Government decided to stop supporting the car manufacturing which caused many to close down. In the place of car manufacturing the Australian Government could support military manufacturing and sell excess stock to the USA, EU and UK. This way Australia has a better defence capability, manufacturing industry and some income to cover the costs.

Nuclear Energy

The N-word. Australia is one of the world largest uranium rich countries in the world but does not use it. Australia could export uranium and become extremely wealthy but the politics are sensitive.

The new nuclear power stations are very safe and Australia is not prone to earth quakes. Nuclear power is half the price of renewables and produces zero carbon. If we decided to develop nuclear energy in Australia we would effectively be a nuclear power as it is easy to go from nuclear energy to nuclear bomb.

Conclusion

As I said it is complicated but worth thinking about and the benefits are not seen until it is too late. Yes, we spend a lot on defence and the 58 new F-35 joint strike fighters will cost a bit but let’s not forget the alternative is a much higher cost. Defence is much bigger than the soldier in the field it is population, manufacture and the N-word. I hope there is peace in the world forever more but I think we should prepare as if war is possible.

ADF personnel deployed to Afghanistan wounded in action

Since Operation SLIPPER commenced, 261 ADF members have been wounded in action in Afghanistan. The breakdown for wounded by year from 2002 onwards is:

| Year | Number | |

| 2002-04 | 4 | |

| 2005 | 2 | |

| 2006 | 10 | |

| 2007 | 19 | |

| 2008 | 26 | |

| 2009 | 37 | |

| 2010 | 65 | (64 soldiers and 1 sailor) |

| 2011 | 50 | |

| 2012 | 33 | (32 soldiers and 1 sailor) |

| 2013 | 15 | (14 soldiers and 1 airman) |

| Total | 261 | (258 soldiers, 2 sailors and 1 airman) |

| as at 28 October 2013 | ||

The types of wounds sustained can be broadly categorised as:

- 1. Amputations,

- 2. Fractures,

- 3. Gun shot wounds,

- 4. Hearing loss,

- 5. Lacerations/contusions,

- 6. Concussion/traumatic brain injury,

- 7. Penetrating fragments, and 8. Multiple severe injuries.

2013

June 22 – Corporal Cameron Stewart Baird MG, 32, from the Special Operations Task Group was killed in small arms fire engagement in Afghanistan.

2012

October 21 – Corporal Scott James Smith, 24, with the Special Operations Task Group was killed in an IED explosion.

August 30 – Private Nathanael Galagher, 23 and Lance Corporal Mervyn McDonald 30, were killed when a ISAF helicopter they were travelling in crashed while attempting to land in Helmand province.

August 29 – Sapper James Martin, 21, Lance Corporal Stjepan Milosevic, 40 and Private Robert Poate, 23, were killed in southern Uruzgan by a man wearing an Afghan army uniform.

July 2 – Sergeant Blaine Flower Diddams, a 40-year-old soldier was killed during an engagement with insurgents while on a partnered mission with Afghan security forces targeting an insurgent commander. He was a member of the Perth-based Special Air Service Regiment.

2011

October 29 – Corporal Ashley Birt, 22, Lance Corporal Luke Gavin, 27 and Captain Bryce Duffy, 26, were killed in an incident reportedly sparked by an Afghan army sergeant turning a machine-gun on Australian soldiers tasked with training him, during a weekly parade inside a forward operating base at Shah Wali Kot, in Kandahar Province.

August 22 – Private Matthew Lambert, 26 was a member of the Mentoring Task Force. He was killed when an improvised explosive device detonated as he was on a night patrol near outpost Patrol Base Anaconda in the Khaz Oruzgan region, about 85km northeast of the main base at Tarin Kowt.

July 4 – Sydney-based 2nd Commando Sergeant Todd Langley, 35, died from a gunshot wound to the head after an incident in southern Afghanistan.

June 6 – Australian soldier Sapper Rowan Jaie Robinson, 23, was shot dead by insurgents in the northern Helmand province.

May 30 – Twenty-five year-old Lance Corporal Andrew Gordon Jones was shot by an Afghan soldier who fled the scene, while another, Lieutenant Marcus Sean Case, 27, died when the Chinook helicopter he was travelling in crashed.

May 23 – Sergeant Brett Wood, 32,was killed conducting clearance operations in southern Afghanistan. This brings the current Australian death toll from the conflict to 24.

February 19 – Sapper Jamie Larcombe, 21, was killed during un-partnered patrol in Oruzgan province, where insurgents launched a coordinated attack with machine gun and small arms fire.

February 2 – Corporal Richard Edward Atkinson, 22, was killed by a roadside bomb while conducting a foot patrol with the Afghan National Army. He was engaged to be married.

2010

August 24 – Lance Corporal Jared MacKinney, 28, was killed in a firefight. The soldier from the 6th Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment was patrolling in the Green Zone in the Oruzgan province, recently handed over by the Dutch, alongside Afghan troops.

August 20 – Private Grant Kirby, 35, and Private Tomas Dale, 21, from the sixth Battalion Royal Australian Regiment, were both killed by an IED (improvised explosive device) which went off when the pair were overseeing an Afghan army patrol in the Baluchi Valley.

August 13 – Trooper Jason Thomas Brown, 29, from Perth’s Special Air Service Regiment, died after being shot during an engagement with insurgents.

July 9 – Private Nathan Bewes, 6th Battalion, of The Royal Australian Regiment is killed by an IED.

June 21 – A helicopter crash not related to enemy fire kills three Australian Army Special Forces soldiers from the 2nd Commando Regiment (formerly known as 4RAR Commando Battalion) – Private Timothy Aplin, Private Scott Palmer, and Private Benjamin Chuck.

June 7 – A Taliban bomb kills Brisbane-based 2nd Combat Engineer Regiment’s Sapper Jacob Moerland, 21, and Sapper Darren Smith, 25, as well as their bomb-sniffing dog.

2009

July 18 – An improvised explosive device claims the life of Private Benjamin Ranaudo, 22, from the 1st battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR) north of Tarin Kowt.

March 19 – Explosive ordnance disposal specialist Sergeant Brett Till, 31, dies during an attempt to defuse a roadside bomb in Oruzgan Province. He is from the Holsworthy-based Incident Response Regiment.

March 16 – A firefight with the Taliban north of Tarin Kowt leaves Corporal Mathew Hopkins, 21, dead. He was a member of Australia’s mentoring and reconstruction taskforce that trains Afghan troops.

January 4 – Private Gregory Michael Sher, 30, a South African-born reservist from Sydney’s 1st Commando Regiment, is killed in a rocket attack in the Oruzgan Province.

2008

[December 17 – Rifleman Stuart Nash, 21, was killed in combat while serving with the British Army in Helmand Province.]

November 27 – An IED blast in Oruzgan kills Lieutenant Michael Fussell, 25, from 4RAR Commando Battalion.

July 8 – The Perth-based Special Air Service Regiment lost its New Zealand-born signaller Sean McCarthy, 25 in an IED blast.

April 27 – A battle with the Taliban in Oruzgan Province kills Lance Corporal Jason Marks, 27, from 4RAR Commando battalion.

2007

November 23 – Taliban fighters kill 4RAR Commando Battalion’s Private Luke Worsley, 26, in Oruzgan Province.

October 25 – SASR Sergeant Matthew Locke dies in a firefight with insurgents in Oruzgan Province.

October 8 – An IED blast in Oruzgan Province claims the life of Trooper David Pearce, 41, from 2/14 2nd/14th Light Horse Regiment (Queensland Mounted Infantry).

2002

February 16 – A patrol vehicle strikes an anti-tank mine, later killing Sergeant Andrew Russell, SASR.

Lest we forget

Reference

2 http://www.globalfirepower.com/countries-listing.asp

Brad’s radio interview on taxi deregulation

Brad’s radio interview on taxi deregulation

My interview with Steve Austin on his radio show Mornings with Steve on ABC radio 612 am.

Old Queenslanders in a New City

Looks like the Federal Government are getting around to dealing with one of the biggest issues in development, heritage restrictions.

More information about the problem here in Brisbane.

An old post of mine which was on Gene Tunny’s blog Queensland Economy Watch.

http://queenslandeconomywatch.wordpress.com/2013/11/15/guest-post-old-queenslanders-in-a-new-city/

Recently, Brisbane’s Lord Mayor Graham Quirk said:

“A leading destination for business and investment, major events and international education, Brisbane is rapidly emerging as a diverse and energised global city with a $135 billion economy.”

Everyone in Brisbane has seen the Old Queenslanders in and around the city. However, you may not know these old buildings are protected by Council regulations. In October of 1995, Council introduced ‘Gray Tape’, a blanket layer of protection over suburbs where the majority of homes had been built before the end of World War II.

It is difficult to see how Brisbane can be a ‘global city’ when most of the population are forced to live in 100 year old wooden boxes. The argument is the old houses are historical and have ‘character’. Well horse and buggies are historical and have character but we are not forced to drive them to work every day. We have museums for these things.

When the rules were made to stop people knocking down the Old Queenslanders, Brisbane was still a small city. Now Brisbane is growing up and needs room for people to live in the city to be close to work. Maintaining the restrictions on development of land close to the CBD of Brisbane is pushing the price of each dwelling up to levels seen in New York and London. Land is limited by nature, but the number of dwellings on the land is limited by Council.

As an example the West End average house price for a renovated Old Queenslander is about $1 million. There are about 1,500 Old Queenslanders in West End at this time. If half of these houses were able to be developed into high-rise residential apartments, at one apartment building per 6 houses, that would provide 125 new apartment buildings. There would be around 50 apartments in each building allowing an extra 6,250 families or about 15,500 people to live close to the city. The other half could be turned into townhouses and new parks. This could be repeated all around our city, brining a cosmopolitan lifestyle to our little city.

New apartment buildings cost about $30 million to build. Allowing developers to build 125 new buildings would provide a large boost to the economy of about $3.7 billion. Then all the families moving in to the new homes would buy furniture and spend in shops, providing much needed economic activity for the city. This sort of development could happen in Paddington, Red Hill, Spring Hill, New Farm, Highgate Hill, Kangaroo Point and East Brisbane. That is $30 billion added to the Queensland economy with no Government funding required.

Fewer people to move from outer suburbs will reduce the pressure on public transport, roads and the environment. More people living in the city would give the Government more money to spend on big events, arts and other entertainment.

Restrictions on building residential high-rise buildings in Brisbane have caused increased costs and long travel times to work, and they have reduced our standard of living and the growth of the economy. The Council restrictions mean fewer people can live close to work and, therefore, we need to pay for more roads, trains, buses and tunnels. The increased travel times to and from work take parents away from their families, increase pollution and reduce our productivity. If we cannot go up, we must go out, and that causes urban sprawl that impacts heavily on the environment.

If Brisbane really wants to become a World City, then we must stop listening to the vocal privileged few who are living in little wooden houses in the middle of the CBD and start developing new stylish homes for our workers. Removing the Grey Tape would allow development of Brisbane where six Old Queenslanders could make way for a block of units which could house hundreds of families.

If we want to keep some of the Old Queenslanders, let’s put them in a historic village out of the operational city of Brisbane. The people who like the old things can go to the historic village and ride horses around on the weekends. We can show our children the funny little houses we lived in before Brisbane was a real city.

Opportunity Cost and the Sunshine Coast Aerospace Precinct

The Sunshine Coast is looking for economic development opportunities which is a great idea however I think some direction is required and a better understanding of how to achieve economic development objectives. One obvious example is the Sunshine Coast Council’s (the Council’s) desire to develop an Aerospace Precinct at its current airport.

The idea of an Aerospace Precinct in itself is not that bad an idea however when you consider the current location of the Sunshine Coast Airport the opportunity cost of the site needs to be considered, see the picture below.

The Sunshine Coast has some of the most beautiful beaches in the world which gives it a competitive and comparative advantage to other regional locations. The current Sunshine Coast Airport is sitting on 51,000 square meters of prime beachfront land. The Sunshine Coast also has ample undeveloped land available away from the beach. Therefore, it would be sensible for the Council to consider selling the beachfront land to allow development and use the funds to build a new airport further inland.

The amount of beachfront land available is almost enough to develop an entire new town on the coast. As we know most people would prefer to live close to the beach if they can and will pay more for that land. Land values alone in surrounding areas of the Sunshine Coast Airport are about $300 per square meter which would indicate the Sunshine Coast Council could sell the land for about $15.8 million.

Airports are very low cost to build as the air strip is basically just a big road which councils build all the time. The land that can be costly to buy but in this situation the land further away from the beach is considerably cheaper than the land close to the beach.

Realestate.com.au advertise land away from the beach on the Sunshine Coast at about $25 per square meter which would cost the Council about $1.2 million to buy the same amount of land as the current airport. That would leave the Council with over $14 million of net sale profits to build a new airport.

There is currently a perfect piece of land for sale out the back of Coolum at $8 million for 316,300 square meters of land next to the highway[1]. The Sunshine Coast Council may want to purchase this land and get started on the new airport. Even a land cost of $8 million would still leave over $7 million for construction.

The economic development benefit of this option would be the increase in current property values near the current airport, new construction of houses on the old airport site and increased population which increases the total economy. According to RP Data the median house price in the next suburb, Coolum is about $415,000 and the typical land size per block is about 571 square meters[2]. Therefore, if the current airport was turned into new housing the area would receive new investment in the region of $37 million[3] (2014 dollars).

Moving the airport inland and allowing the development of the old site would increase the liveability of the current airport site, increase economic development by at least $37 million and still enable the Council to develop its Aerospace Precinct.

Queensland Taxi Licenses and Drunken Violence

Queensland’s taxi regulations are costing the Brisbane public over $80 million per year and may be contributing to drunken violence. Queensland’s Department of Transport constrains the number of taxi licenses which increases the prices of taxi fares and long periods of waiting at peak periods. The long lines of drunk people in the early morning on the weekend waiting for a taxi are one of the sources of drunken violence. Deregulation of the taxi industry will reduce the cost of taxis by an estimated half the current fare and reduce waiting time for customers. Getting party goer’s people off the street quickly and cheaply will assist in reducing drunken violence.

Queensland, like most other States in Australia has a heavily regulated taxi industry. The Queensland regulations set the price and limit the number of licenses issued. Restrictions on the industry are imposed by the State Government in an effort to maintain high standards of safety and quality which can be a problem with markets where there is a high level of limited information available to users (asymmetric information). However, there are much more efficient methods of dealing with these issues in markets as was pointed out by the Productivity Commission’s (PC) report on the Regulation of the Taxi industry in 1999[1].

Taxi users have difficulty in assessing the safety and quality of service associated with a particular taxi. This may be less of a problem for frequent users who, over time, become familiar with (say) the calibre of the drivers and the cleanliness of vehicles attached to a particular taxi company. Nonetheless, with large numbers of individual taxi owners, significant variations in quality standards can exist, even between taxis in the same fleet. And even frequent users have limited capacity to assess some elements of safety and quality (e.g. the roadworthiness of the vehicle).

Brisbane Taxi Regulation Costs

A report by Gaunt and Black in 1996 examined the Brisbane taxi industry and found in 1993, taxi regulation had resulted in a Brisbane taxi plate having a value of $190 000, reflecting 228 fewer cabs than would arise under a competitive regime. Gaunt and Black’s report attempted to measure the cost to the Queensland economy:

‘The public or consumer interest has suffered an estimated $20.67 million annual loss of wealth in 1993, while between $11 million and $19.1 million of this loss has been picked up by the politically powerful licence holder lobby and between $1.48 million and $9.55 million has been lost to society with no group directly benefiting [the deadweight loss]’.

Today a taxi license in Brisbane costs around $510,000 which is about 2.7 times the price of a license in 1993. If Gaunt and Black were correct and their measure of annual loss of wealth loss also increased by the same proportion, then the 2013 loss was $55.48 million plus $25.63 million in deadweight loss. That is $81.12 million loss to the Brisbane economy in one year or the net present value of this cost in perpetuity is about $1.2 billion[2].

Therefore, Brisbane people are paying much more for taxi fares then they would have to if the market was deregulated and they would not have to spend hours waiting for a taxi in peak periods. When I apply a standard regulators building block model to estimate the required returns for a taxi in Brisbane I found the license requirement at least doubles the cost of a taxi fare.

The owner of the license will require an annual return of at least $50,000 on their investment of $510,000 which is around half the taxi owner’s required return. There does not appear to be any reason for a taxi license to cost this much except the number of licenses are constrained by the State Government Department of Transport.

Alternative Regulation to a Supply Constraint

As mentioned above the stated reason for constraining licenses is to ensure safety and standards. However, the PC report has carefully laid out some simple light-handed regulatory methods of maintaining the safety and standards while opening the market to competition.

Safety

Taxis are driven much more than the standard car would be expected to drive so if the issue is how we ensure the taxis are safe then an increase in the number of times a roadworthy test is done could be increased. Anyone operating a taxi may be required to do a roadworthy two or three times in a year. Also, the competition for service would allow taxi owners to increase their standards to attract more market share. As pointed out by the PC report:

In terms of the taxi industry, this could imply that, rather than promulgating compulsory standards through regulation, governments (or possibly private organisations) could offer voluntary certification to taxi operators.

Prices

Fare controls could be removed and replaced with the PC’s recommended posted prices. Posted prices would require all taxis to display their standard fares which they can change by notifying the Queensland Transport Department. This pricing method has the advantage that any user can get in the taxi knowing the price and does not have to haggle with the driver. Posting the prices on the window of the taxi allows people to choose between taxis selecting on price and standard.

Connection with Drunken Violence

Unlimited number of taxi licenses would greatly increase the service to people in Brisbane. It may also assist to some extent with the drunken violence in the night club districts at peak times. Anyone who has tried to get a taxi on a Friday or Saturday night will know the extreme waiting times and problems in the lines.

If there were many more taxis and the fares were half what they are now and there would be less people standing around at 3.00am drunk waiting for a taxi. When people are drunk, tired and cannot get home they become agitated then they are more likely to get in to a fight. If they could just come out of a club and get in a taxi which would run them home for half the current rate there would be less people and less trouble in these areas at peak times.

People would be less likely to walk home and therefore be less likely to get into trouble. People walking home from a big night are vulnerable to attack from criminals. These people are also more likely to cause damage to other people’s property or be picked up by Police for other infringements.

Other Possible Positives

Deregulation would enable a large amount of quick response taxis to be available for a wide range of people and purposes providing many benefits, including:

- people would be less likely to drink drive because it would be cheap and easy to take a taxi;

- local people that drive to work may decide to by a mini bus and drive some other people at the same time;

- we could have taxi utes that can come over and pick up an item for easy movement; or

- a person with time on their hands may decide to drive people from the local area to the train station for a very low price.

The point is we don’t know all the benefits of deregulation until it happens but we do know the current situation is not meeting all our needs and is costing us much more than it benefits.

How do we get this to happen?

There are three main approaches to deregulation of the taxi industry suggested by the PC report. The first involves buying back all the licenses from the current owners as compensation to the industry for deregulation. The problem with this is the Queensland Treasury would have a heart attack and recommend against the deregulation. At over $500,000 per license for every 1,000 license payments the State would be up for $50 million which gets very expensive very quickly.

Another approach explored by the PC report is to just flood the market with new taxi licenses which would make the price for a license crash. The problem with this approach would be political backlash from the taxi industry and anyone who felt bad for them. Politically, this approach would be bound to fail.

The most likely approach to succeed is the third which is a middle road of an announced slow increase of licenses over a period of years combined with some industry compensation. This is the approach taken in Victoria which has started to have the desired effect. On the Victorian reform announcement the license fee in Melbourne reduced from over $500,000 to $350,000.

Other Locations of Taxi Reforms

The Northern Territory and New Zealand have already deregulated their taxi industries which have both had mixed reports of success and problems.

Queensland Ports For Sale

Recently, the Newman Government announced it is considering selling some of the Queensland Government owned ports, namely Gladstone and Townsville. This would be a tremendous step forward for Queensland, which would benefit the economy for many years to come.

The benefits from selling these ports would be direct and indirect to the Queensland public. The direct benefit would be an estimated $1.5 to $2.0 billion cash injection from the sale proceeds, reduced debt and reduced future subsidisations. The indirect benefits would come from increased efficiency, a better allocation of Government resources and better trade opportunities. Better trade would be possible as the private company with a profit motive would seek to maximise throughput to increase its profits. This is in contrast to a Government owned port that does not have a profit motive only a direction to export certain products.

Typical arguments against selling Government assets are centred on the public benefit, foreign interests may restrict Australian access or we are selling our future. These arguments are fear campaigns based on misinformation. As mentioned above, Queensland would benefit much more from selling the ports rather than owning them.

Gladstone and Townsville are two very different ports with their own problems. Gladstone is a profitable port which is mainly used for exporting coal and Townsville is a heavily subsidised unprofitable port. Selling the profitable port of Gladstone will gain a high selling price for the Government. It can then reallocate that capital to core Government activity such as hospitals, schools and roads. The port will become more efficient being run by a private company providing more benefit to the Queensland economy, and tax payers will have lower debt and/or more Government services.

Townsville Port is unprofitable and is subsidised by the Queensland tax payer by approximately $15 million per year. Subsidising a port is not benefiting the economy as much as we are paying making it a net loss to the Queensland economy. Part of the cause of this ports loss making problem is that Queensland Governments have historically been captured by special interest groups, and past Governments have allowed low rate contracts. Government owned ports undercharge industrial and agricultural exporters. Selling the Townsville Port would allow the new owners to change its business structure, relationships and focus on profitable activity. Again, the Queensland Government could use the sale proceeds to reduce debt and pay for core Government activities. The Government would also gain from not having to pay subsidies to the port for the rest of its life. Having strong profitable privately-run ports in Queensland would be a great positive for the economy and the people of Queensland.

The suggestion that a foreign interest could or would own the ports and restrict Australian access is not a real problem. In most cases any foreign owner will want the same outcome as we do, a profitable well-run port delivering maximum services at commercial rates. There can be problems with ports being monopoly providers however that problem is controlled through regulation by the Queensland Government’s competition watchdog, the Queensland Competition Authority. The Government always has the option to take back the port if for some reason the foreign interest decided to stop or restrict Australian access. Ultimately, the Government always maintains ownership of all land in Australia.

The issue here is what is more beneficial to Queensland: Government ownership or private ownership. In most cases it will be more beneficial to the wider community for a private company to own any business. The Government can assist business by setting rules, regulations and providing connecting infrastructure. When the Government wants to provide a subsidy to an industry or special interest group it is good public policy to make it transparent rather than hiding it in lower prices.

For example if the Government wants to assist grain and cattle producers to export its products it is more efficient to pay them directly for the transport cost rather than own the ports and sell services below market rates. Government ownership of any asset reduces it efficiency, effectiveness and flexibility. Efficiency is reduced due to the lack of profit motive. The profit motive is a great way for any business to continuously look for opportunity to improve its service in terms of efficiency, effectiveness and flexibility. If a private company does not maintain close attention to what its customers want and provide that service at the cheapest rate, then a competitor can potentially take the business and provide the service at the lower price.

Government businesses do not have the same pressure to provide efficient, effective and flexible services. If a Government business does not provide the best possible service there is very little anyone can do and the service will just continue to provide poor inflexible service with minimal benefits to the community.

Ports are the gateway for the rest of the world to business in Australia. If our ports are not run well then the rest of our businesses will suffer, reducing the benefit to Queenslanders.

New World

This could be Brisbane if Council would allow it.

Recent Comments